Summary of seminar held in Helsinki 19 November 2019

“At current fertility rates, we Europeans are basically breeding ourselves out of existence.” This was one of the comments made by Dr Nils Erik Forsgård, Director of Magma, during his opening remarks at the Ralf Dahrendorf Roundtable on Population Decline and Its Effects in Europe, organised in Helsinki on 19 November 2019. Europe as a whole is facing a severe demographic challenge. While the exact numbers and reasons for them vary – an interesting point in fact is that the life expectancy for men living in Glasgow in Scotland, for instance, is lower than for men living in the Gaza strip – the trend is the same. Fewer babies are being born and the population of Europe is growing older. While a fertility rate of around 2.1 per woman is perceived to be the replacement level in developed countries, 1.59 was the rate in the EU in 2017. In Sweden, the rapidly growing amount pf people older than 80 years would require a new care home for the elderly to be opened every fourth day for the upcoming six years. At the same time, the African continent stays young: “The pull of a rich and old and grey Europe on poor and young Africans in search of opportunity and income will be immense”, thinks Dr. Forsgård; “We here in Europe should prepare ourselves much, much better for the effects of this transition in the upcoming decades.”

Fertility not the only crucial factor

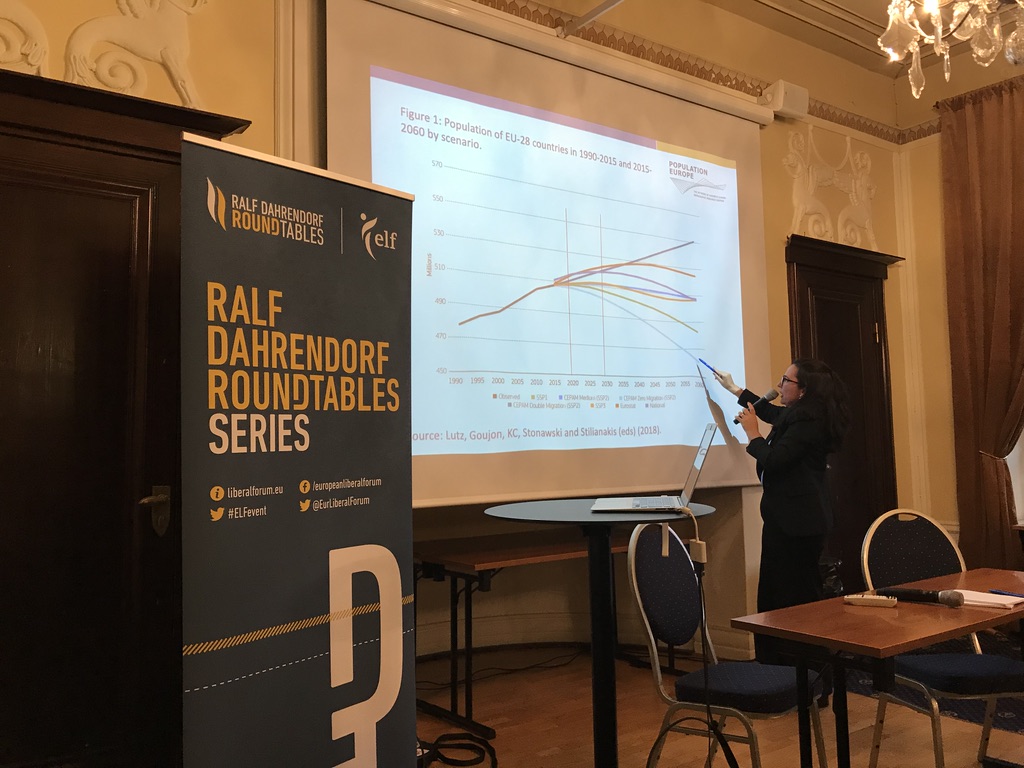

Dr Daniela Vono de Vilhena of Population Europe/the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, warned us not to be too alarmist: The world population is not growing at the same rate as it did some decades ago, but it’s still growing. Also, the birth rate in Europe decreased at a slower pace between 2000 and 2017 than before. Nevertheless, she observed: Africa and Asia remain the continents of the children of the future. Few changes in fertility levels are expected to occur for the rest of the world: in Europe, demographers are not expecting fertility trends to drastically change in the upcoming decades. According to Vono de Vilhena, even if birth rates were to increase it would not have a big effect on population numbers. Pragmatic migration policies, therefore, are and will be essential to maintain a healthy population structure in our region, she underlined.

Amongst other factors shaping our population structure, such as age, gender, education levels, place of residence and labour force participation, changes are expected to happen at least in the age composition of the population and on the levels of educational attainment. The proportion of individuals aged 70 and more is expected to keep growing in the future, whereas the proportion of other age groups are expected to decrease. According to data from the Centre of Expertise on Population and Migration (CEPAM), half of the population of EU-28 was at least 43 years old (median age) in 2015. By 2060, however, 50 % of the population is expected to be at an age above 50 years old. There is, therefore, a need to look at the situation in all its complexity, and to better prepare our societies for an older population structure. An ageing population does not have to be a burden. Recognising the potential of older persons, encouraging longer working life and promoting healthy lifestyles are recommendations that are often promoted by experts in the field.

Education levels are also expected to rise in Europe in the next decades, bringing with it positive side effects for a healthier population. Higher education levels are accompanied by decreases in fertility and mortality, and by improvements on the health status of the population. Individuals with higher education have higher life expectancy. At the same time, our young people stay at home longer and start families later. In 2019, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) in the UK said that over the last two decades, there has been a 46 % increase in the number of young people aged 20–34 living with their parents. Over the same period, average house prices have tripled from about £97,000 to £288,000. Factors that shape both our population structure and population size is therefore very much within the scope of policy and economics.

Finland’s particular challenge

Prof. Emma Galli, Scientific Director, Fondazione Luigi Einaudi, Italy, Andrea Virág, researcher of the Republikon Institute, Hungary and Prof. Anna Rotkirch, Director of the Population Research Institute at the Family Federation of Finland gave insights into the ways in which demography and the welfare state systems have developed in southern Europe, eastern Europe (V4 countries) and Scandinavia/Finland. Amongst these, Finland stands out with its total fertility rate for 2019 expecting to land at as low as 1.33 children per woman. Though part of a general trend, the numbers for Finland are alarming. Prof. Rotkirch gave three possible explanations for this: 1) Lower fertility ideals & more uncertain intentions: there seems to be a greater focus on work as the meaning of life (‘workism’) and a belief that living with young children is terrible (‘lapsiperhekamaluus’). The number of women aged 20–39 who do not wish to have children at all has grown from 1 % in 1977 to 11 % in 2018 in Finland. 2) High previous proportions of childlessness might make not having children more ‘normal’; is there vulnerability to a ‘low fertility trap’? 3) The generation of two financial crises might feel that having children creates a financial risk.

Demographic development supporting populism?

In Hungary, where fertility rates are just slightly above Finland’s, and where young people emigrate at a substantial rate – there is even talk of ‘London as the second largest Hungarian city’ – the countryside especially is quickly losing its population. Ms Virág showed how today, almost a quarter or all Hungarians live in one of the five largest cities. The ruling Fidesz-KNDP coalition has consequently made families its main priority, introducing a family protection action plan in 2019. According to the plan, families can inter alia receive support for buying a new home (levels depending on the amount of children), a mortgage reduction if the number of children are two or more, support for buying a car if the number of children are three or more, and mothers with four children or more do not have to pay income tax. A child support allowance has also been introduced for grandparents. Increasingly, family seems to be high on the agenda for many populist parties, whose support is growing particularly in the depopulating and economically stagnant rural areas. Population decline in Europe indeed appears to be playing into the hands of populism. “It could and probably should be said” commented Dr Forsgård, “that the current demographic development in Europe is assisting in the growth of populist parties all over the continent”.

Solutions in the broad picture

There was active discussion throughout the Roundtable seminar, with the audience actively suggesting other both reasons and solutions for Europe’s demographic challenges. As summarised by Dr Vono de Vilhena: solutions for demographic problems are not necessarily found in demographics, but in very basic social, economic and family policies, such as:

- Better usage of the potentials we already have: immigrants, women, older and young people.

- Investment in human capital.

- Reduction of social inequalities and guaranteeing an adequate minimum income for all.

- Achieving inclusive, fair and sustainable systems of health and social security.

To this could be added an example from Norway, where quotas for fathers have been introduced within the legal parental leave that all new parents are allowed to take. A recent study showed that the proportion of fathers using the father’s quota was more important than how much leave fathers actually take (gender equality indicator). This engagement by fathers, which has become a social norm in Norway, could be one of the reasons why the two-child norm has been maintained in the country.

As commented by director Forsgård: “Let us not be too pessimistic or fatalistic. Individuals and nations still have the power and the capacity to make changes and decisions that will change the future and its demography.” This Ralf Dahrendorf Roundtable provided a lot of useful facts and recommendations to build on for all of Europe in coming decades, when we need to find new solutions for upholding the social and economic fabric of our societies.

Disclaimer:

This event was organised/financed by the European Liberal Forum with the financial support of the European Parliament. Neither the European Parliament nor the European Liberal Forum are responsible for the content, or for any use that may be made of it.